Last updated: 20 September 2024

What is neurodiversity?

Definitions of neurodiversity

‘Neurodiversity’ is the umbrella term used to describe the neurological ways that people process information that are different from the accepted ‘norm’. It often runs in families, and occurs in all genders, races, cultures, socio-economic groups, and intelligence scales.

The list of conditions that come under the neurodiversity label can vary, but the ones we are most commonly asked about are:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) – also known as autism

- Dyscalculia

- Dyslexia

- Developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) – also known as dyspraxia.

You can find a factsheet on each of the most common neurodiversity labels in this section of the Toolkit or by clicking the hyperlinks above. There are other conditions are sometimes included under the ‘neurodiversity’ label or closely linked to it due to common features. For example, cluttering and Tourette’s, or menopause. Information on these and other conditions that can be included under the term neurodiversity can be found in the ‘Conditions associated with neurodiversity’ below.

Unlike some other terminology, ‘neurodiversity’ includes strengths as well as some of the challenges and barriers that neurodivergent people may experience. In other words, it looks at the whole person and their environment, not just the perceived negatives.

Neurodiversity is ‘diverse,’ meaning no two people will be alike. In fact, they can have the same condition and have very different profiles from each other.

How many people are neurodivergent?

A 2020 study estimates that one in five to seven (or 15-20 per cent) of the global population is neurodivergent. This represents a significant number of employees, customers and service users.

It is difficult to gather accurate data for many reasons:

- A lack of globally recognised definitions

- Stigma

- Poor access to diagnostic assessments

- A historic lack of consistent assessment methods and criteria

- A historical lack of research

- An assumption in many cases that boys and children are most often affected.

Aidan Healy – How to read stats on neurodiversity

Aidan Healy, Chair at Lexxic, spoke at our 2022 Global Conference about how to make sense of statistics around neurodiversity. He also explains some of the challenges of interpreting the data.

The ‘spiky profile’

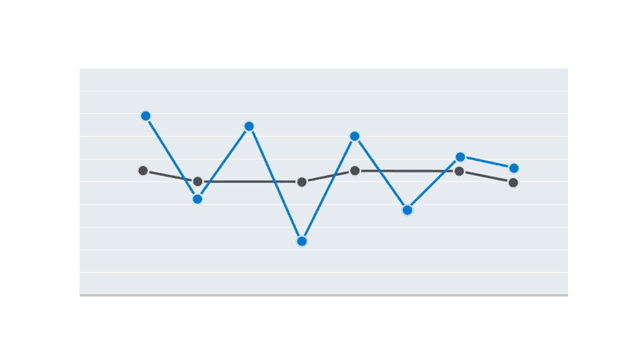

The ‘spiky profile’ visually demonstrates a person’s strengths in different areas. It aims to show how neurodivergent people may find different things much easier or harder than non-neurodivergent people.

A person who is not neurodivergent will have a relatively stable and consistent profile with a smaller difference between their highest and lowest areas. This is represented in black in the example below. A neurodivergent person will have much larger deviations, resulting in the ‘spiky profile’ shown by the blue line in the example below.

No two profiles are the same – even for people with the same neurodiverse condition. The profile demonstrates the range of strengths and challenges experienced by a neurodivergent person and why they sometimes appear inconsistent in their work, social skills, focus, energy and so on compared to their peers. For example, many tasks involve different skills or processes. If a person has a stable profile, they may find some aspects slightly more difficult than others. For the neurodivergent person, they may find some aspects very easy and others very hard.

Aidan Healy – Two sides of the same coin

Aidan Healy, Chair at Lexxic, spoke at our 2022 Global Conference about reframing ‘deficit’- and ‘disorder’-based understandings of neurodiversity. He explains that someone who may be seen as ‘deficient’ in one environment can actually have a related strength in another environment – these are two sides of the same coin.

Jean Tennant – Technical Writer, BDF

Jean is a Technical Writer who works to create and maintain the resources on our Knowledge Hub, including this Toolkit.

Here she introduces herself and talks about her likes and dislikes as a person with dyslexia.

Executive functioning

Many of the barriers neurodivergent people experience are related to executive function. It is often talked about in the context of neurodiversity and is an important concept.

Executive functions are the mental processes we need to be able to carry out key skills. There are three main types of brain function that are required for good executive function:

- Working memory – the temporary holding of information for immediate use such as problem-solving, arithmetic, following directions.

- Self-regulation – the ability to control behaviours, actions and emotions, such as following rules.

- Mental flexibility – being able to adapt appropriately and in a timely way to new situations, such as switching work tasks.

These can then be broken down into a number of skills needed in life and work including:

- Planning and organisation

- Prioritisation

- Motivation / starting and finishing tasks

- Time management

- Focusing

- Flexibility

- Short-term working memory

- Impulse control / self-regulation

- Emotion control

- Communication.

All the above are usually interlinked. See the adjustments section of this Toolkit for advice on managing employees with barriers related to specific processes listed above.

Podcast: ‘If you don’t mind me asking…’ with Michael Vermeersch

Accessibility Go To Market Manager at Microsoft Michael Vermeersch talks about his career so far, life, insights from friends and family – and how the illuminating autism diagnosis he received led to a new level of self-advocacy.

You can connect with Michael here: Linkedin and Twitter.

Conditions associated with neurodiversity

This section looks at the less common conditions associated with neurodiversity. Some can be present from birth and others develop later in life. Some may be temporary.

Tourette’s syndrome

Tourette’s syndrome is a neurological condition that causes a person to ‘tic’.

Tics are sudden, repetitive, involuntary movements or sounds which can be painful and tiring. For example, repetitive rapid blinking, twitching of the head or making tongue-clicking noises.

See our factsheet on Tourette’s syndrome for more information.

Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia is a condition that affects an individual’s ability to write. It rarely occurs on its own. It is often accompanied by other neurodiverse conditions. It shares many characteristics with dyslexia and dyspraxia.

It affects an individual’s ability to write. This can be due to poor fine motor co-ordination and spatial perception. Language skills are also sometimes affected. This results in illegible handwriting which is not within the structures of lines or margins. The individual often writes slowly. They may also have difficulty with grammar, sentence structure and organising thoughts on paper.

Unlike difficulty with writing caused by illness or injury later in life (known as ‘agraphia’), dysgraphia is present from birth.

Acquired brain injury

This term covers any brain damage that occurs after birth. It can be direct trauma following an accident, disease, infection, or a lack of oxygen. The location of the damage will determine what challenges the individual experiences.

Brain injury can affect areas such as:

- Memory

- Concentration

- Communication

- Information processing (such as auditory or visual information)

- Time management

- Emotions (such as empathy and resilience).

An individual with an acquired brain injury may experience new strengths or weaknesses in single or multiple areas.

Menopause

Researchers are starting to look at the links between female hormone fluctuations and neurocognition, especially relating to the menopause. The effects of menopause can sometimes be similar to common neurodiverse conditions, such as changes around sensory sensitivity, memory and communication.

Menopause can also cause changes in pre-existing neurodiverse conditions. Some neurodivergent women find that they experience their condition differently during menopause, often with increased severity.

Many menopausal and perimenopausal women may benefit from adjustments suggested for neurodivergent individuals due to the similarity of challenges.

As always, talk to the individual about the barriers they are facing and work with them, and relevant experts, (such as Occupational Health), to find solutions.

Co-occurring neurodivergent conditions

People with one neurodiverse condition are more likely than not to have at least one other neurodiverse condition (according to Do-IT Profiler). This is known as ‘co-occurrence.’ This will impact how their neurodiversity affects them as an individual. It will also impact the adjustments that are needed to help them function in a world that isn’t always designed for them.

The 2017 Westminster AchieveAbility Commission for Dyslexia and Neurodivergence research report [PDF] showed most respondents had more than one neurodiversity label.

The experience of multiple neurodiverse conditions

Some characteristics are specific to one neurodiverse condition, while others are common to many neurodiverse conditions. For example, reading speed and accuracy challenges are associated primarily with dyslexia, but poor short-term working memory is common in dyslexia and ADHD.

A person with co-occurring neurodiverse conditions may not experience them as separate conditions. However, they may find that it affects a wider range of processes. The degree of positive or negative impact will depend on many interlinked factors. For example, a working environment can significantly affect a person’s work rate, accuracy and physical and mental wellbeing.

Some neurodiverse co-occurring conditions can appear to contradict each other and cancel out some symptoms. For example, a person can be over and under stimulated at the same time. Rather than reducing the effects for the person, the effect is often multiplied.

As with all disabilities, remember that each person is an individual. Even with one neurodiverse condition, the experience is unique to the individual. The same is true for people with co-occurring neurodiverse conditions.

Neurodiversity and co-morbidity

Above we said that having more than one neurodiverse condition is known as ‘co-occurrence.’ When we talk about having a neurodiverse condition and another condition that is unrelated to neurodiversity, we use the term ‘co-morbidity.’

People with neurodiverse conditions can be more likely to experience other symptoms or conditions that are not directly related to neurodiversity. Living with a neurodiverse condition can lead to issues with mental health. It can also be associated with other health conditions.

Mental health

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Addiction

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Self-harm (including suicidal thoughts)

- Eating disorders

- Anger

- Low self-confidence and self-esteem

- Burnout – due to difficulty pacing work and/or trying to meet the others’ expectations.

See our Mental Health Toolkit for more information.

Other

- Migraines

- Frequent headaches

- Fatigue

- Stomach and bowel conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome

- Hypermobility – such as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

- Pain due to constant physical tension

- Allergies

- Skin conditions may be worse due to neurodiversity-related stress.

Many of these conditions can be prevented or their severity reduced with appropriate prevention such as training and adjustments. Others will need a combination of these plus medication and other forms of treatment such as counselling, diet and exercise.

If you require this content in a different format, contact enquiries@businessdisabilityforum.org.uk.

© This resource and the information contained therein are subject to copyright and remain the property of the Business Disability Forum. They are for reference only and must not be copied or distributed without prior permission.