- Making information inclusive and accessible

- Inclusive language: What it is and why it is important

- Using inclusive language: Top tips

- How to use design features to create accessible communications

- Alternative formats: What they are and why they are important

- How to use images in an accessible and inclusive way

- How to make accessible infographics

- How to create accessible video and audio content

- Understanding diverse communication needs

- How to create accessible Word documents

- How to create accessible PDFs

- How to write accessible emails

- How to make social media posts accessible

- How to host inclusive meetings: Communication checklists

- Creating accessible PowerPoints: 12 top tips

- How to design accessible leaflets and brochures

- How to design accessible signage

Last updated: 9 June 2025

Making information inclusive and accessible

The following tips will help you to plan your communications so that they are as inclusive and accessible as possible to disabled people. These tips are intended to act as reminders. There is more information in the ‘practical resources’ section of this toolkit on all the topics covered in this document.

Remember, thinking about inclusion at the beginning of a project or piece of communication is really important. The more inclusive you make your piece of communication now, the less time you will have to spend on making it accessible, later.

We know that not all communication can be planned. It is important to be realistic about the time that is available to you. But the more you use these tips, the better you will become at making all your communication accessible.

Top tips

- Think about your audiences and the communication channels they use. Are you providing information in the right way? If time and resources allow, build in time to trial your communication with a customer panel and ask for feedback.

- Think about your message. Will your message resonate with your audiences? Is the language inclusive? Will anyone feel excluded or disempowered by your message?

- Think about your writing style. Are you writing in plain English? Check the length of your sentences to make sure they are not too long or overly complex. Is the language accessible and inclusive? Explain or remove any technical terms if they are not accessible to your audience. Consider whether your writing style is appropriate to your audience. Writing in a formal way may seem appropriate, but it can make your communication inaccessible to some people.

- Think about colours and fonts. Use a minimum font size of 12 point in any written communication and a sans serif font. Make sure words and numbers can be easily read. Use sentence case and left align any text. Check that there is strong colour contrast between the text and the background colour.

- Think about the images you are using. Are they inclusive? Do they represent your audiences in a positive and realistic way? If you are creating a digital document, have you provided Alternative Text for the images or graphics you have used?

- Think about any video content you are using. Is it captioned? Is it representative of your audiences? Does it represent your audiences in a positive and realistic way? Is the language used in the video accessible and inclusive?

- Think about any audio content you are using. Is there a transcript available? Is the language used in the audio accessible and inclusive? Is the recording clear?

- Offer alternative formats. Make sure your communication is available in other formats, such as audio, Easy Read, Braille and large print. Choose the formats which are most suited to the needs of your audience. Tell people that these alternative formats are available and how to access them. Remember that not everyone can access digital formats.

- Ask for feedback. Ask people to feedback on your communications. Consider creating a customer panel or consulting with your disability network. Make sure the panel is representative. Use any feedback to make your future communications more inclusive and accessible.

Inclusive language: What it is and why it is important

The words that we use to talk about disability are important. Our choice of words can make someone feel engaged and included or ignored and excluded.

Unfortunately, many unhelpful and negative stereotypes continue to exist around disability. Using words or phrases without thinking about their meaning can reinforce these stereotypes.

About this resource

This resource is for:

- Anyone who wants to find out how to talk about disability in an inclusive way.

- Those working in communication roles or working with internal or external communication teams and agencies.

- Those working in HR or management roles.

- Those working in customer facing roles.

In this resource, you will find general tips about out how to talk about disability

as well as language to use and to avoid. Whilst most of the advice included here is widely accepted, the debate around language and disability is ongoing as language continues to evolve.

Regularly reviewing the language your organisation uses is important and makes sense. Involve your disability networks and customer panels in the process. It is also important to think about inclusive language when reviewing your brand guidelines, house style guides , and communication policies more widely.

Ask don’t assume

The language we use to describe ourselves is a very personal thing. Disability is just one aspect of who a person is. Always ask the person the language they prefer. They may not wish you to mention their disability at all or they may prefer you use or avoid certain words. It is always best to check.

But, don’t let the thought of using the wrong words put you off. Most disabled people won’t mind if you get it wrong if your intention was right. Context is often as important as the words themselves.

Using inclusive language: Top tips

Ask someone the language they would like you to use. If you are unsure, then ask. Don’t make assumptions.

Focus on removing barriers. Having a disability is just one aspect of a who a person is. Try not to define someone by their disability. Often, it is not necessary or appropriate to mention a person’s disability. Ask what you can do to make things easier for that person rather than about their disability.

Use language that everyone can identify with. A person may be defined as disabled under the law but may not regard themselves as having a disability or ever use the term ‘disabled’ to describe themselves. As an example, people who use British Sign Language, and who identify as part of the deaf community, may prefer to be referred to as ‘Deaf’ with a capital ‘D’. Someone who has autism or dyslexia may prefer ‘neurodiverse’ or ‘autistic’ or ‘dyslexic’.

Avoid emotive language. This includes terms such as ‘victim’ and ‘sufferer’, unless the person themselves chooses to use them. It also includes terms which disempower disabled people, such as “vulnerable”, “frail” and “dependent”.

Avoid terms which are patronising. Don’t imply that someone is ‘inspiring’, ‘brave’ or a ‘superhero’ just because they have a disability.

Use neutral language. For example, use terms such as ‘condition’ instead of terms such as ‘problem’ or ‘issue’, which some people find negative.

Avoid collective nouns. Terms such as ‘the disabled’ or ‘the blind’ suggest that people are part of a uniform group, rather than individuals with their own preferences and identity.

In general, avoid medical terms. Terms such as ‘diagnosis of’ or ‘illness’, may cause offence, although some people choose to use them about themselves. Of course, these terms may be the most appropriate and necessary if you are writing in a medical context. But it is still good to be aware of how they can be viewed by disabled people and people with long term conditions.

Avoid phrases with a negative connotation. Most everyday phrases such as ‘see you later’ or ‘look forward to hearing from you’ are acceptable to someone who is blind or D/deaf. The exception is if the phrase has a negative connotation, such as ‘to turn a blind eye’ or ‘it fell on deaf ears’.

Do not ask people to ‘declare or disclose’ their disability. Some people are ok with this but many others aren’t. It is safer to use plainer language, such as “tell us if you have a disability or condition” or simply ask if people need an adjustment. It is good practice to ask everyone if you can do anything differently to make things easier for them. Remember everyone has preferences regardless of whether or not they have a disability. Business Disability Forum discusses this topic further in an article on inclusive language published by Includr.

Consider your audience. Generally, if writing for a UK audience, then ‘disabled people’ is often preferred over ‘people with disabilities’. ‘Disabled people’ recognises that people are ‘disabled’ by society’s response to them or by their long-term condition. This is called identify first language. If communicating with a global audience, then ‘people with disabilities’ is more widely used. This is called people first language and emphasises the person over their disability.

Take into account cultural meaning. The words and phrases mentioned in this resource relate to the use of English in the UK. Different words will be viewed as acceptable and unacceptable in other languages and cultures. It is important to take this into consideration when translating any information into another language. You can find out more about communicating with global audiences in our Global Guide, ‘Lost in translation? A global guide to the language of disability‘.

Our video, ‘Disability and language: Are you afraid of getting it wrong?’ summarises some of the key messages.

Words to use and words to avoid

Before mentioning a person’s disability, always consider whether it is necessary or appropriate to do so.

If you do need to mention a particular disability or disabilities, make sure the language you use is accurate and doesn’t cause people to feel excluded.

Please note that some of the words used in the following ‘Avoid’ sections may cause offence. We have included them to help increase understanding. We do not endorse their wider use.

- Use: a person with a mental health condition

- Avoid: mental, schizo, psycho, mad

- Use: disabled person, person with a disability, person with a long-term condition

- Avoid: cripple, invalid, or describing disabled people generally as ‘unwell’

- Use: someone who has….

- Avoid: victim of or sufferer

- Use: a person with dwarfism, or someone of short stature. Note that some people prefer ‘dwarf’

- Avoid: midget

- Use: seizures

- Avoid: fits or spells

- Use: a person with a learning disability, or someone with a learning disability

- Avoid: mentally handicapped, retarded, slow

- Use: brain injury

- Avoid: brain damaged

- Use: a wheelchair user

- Avoid: wheelchair bound, confined to a wheelchair

- Use: a person with a disfigurement or visible difference

- Avoid: deformed

- Disfigurement is a legal term in the UK’s Equality Act, referring to people whose visible difference amounts to a disability and confers protection from disability discrimination. We recommend using the term ‘visible difference’ unless referring specifically to the legal protections related to disfigurement under the Equality Act. See our factsheet on visible differences for more information.

- Use: blind people, people who are blind, deaf people, Deaf people, people who are deaf, disabled people, people with disabilities

- Avoid: the blind, the deaf or the disabled.

How to write in an accessible way

Written communication is an important part of most people’s job.

It may just be a quick email or a lengthy report. Either way, how we write can affect the clarity of our communication. Thinking about accessibility when we write will make sure our message gets through to everyone.

About this resource

This resource is for:

- Anyone who want to find out how to make their written communication more accessible.

- Anyone interested in finding out more about disability and inclusion.

In this resource, you will find out why writing accessibly is important. You will also find top tips to help you make you improve your own writing.

Writing in an accessible way: Why it’s important

Writing in an accessible way means using language and sentence structures which our audiences will find easy to understand. The easier it is to understand the more effective our piece of communication is likely to be.

Meeting the needs of your audience

If we are writing to someone we know well, then it can be easy to make ourselves understood. We are likely to have shared vocabulary and have a good understanding of how each other likes to communicate.

In a work situation, however, we often have to communicate with colleagues and customers who we may not know as well, or at all. We may also have to communicate with a lot of people at once. This means that we need to write in way which is accessible to as many people possible.

Formal v informal language

Often, we may choose to use more formal language in business communication than we do outside of work. We may be concerned that sounding informal may suggest a lack of respect for the reader.

There is nothing wrong with using formal language if we are sure that it is appropriate for the audience and communicates the message we want it to. Usually, our message will come across clearer, if we use everyday language, which is easier to understand for everyone.

Accessibility and literacy

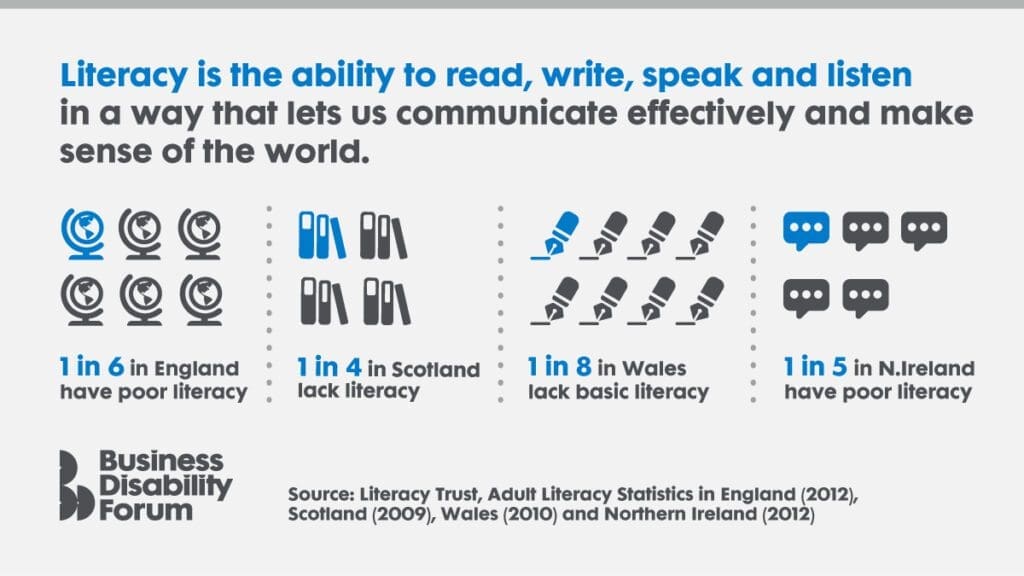

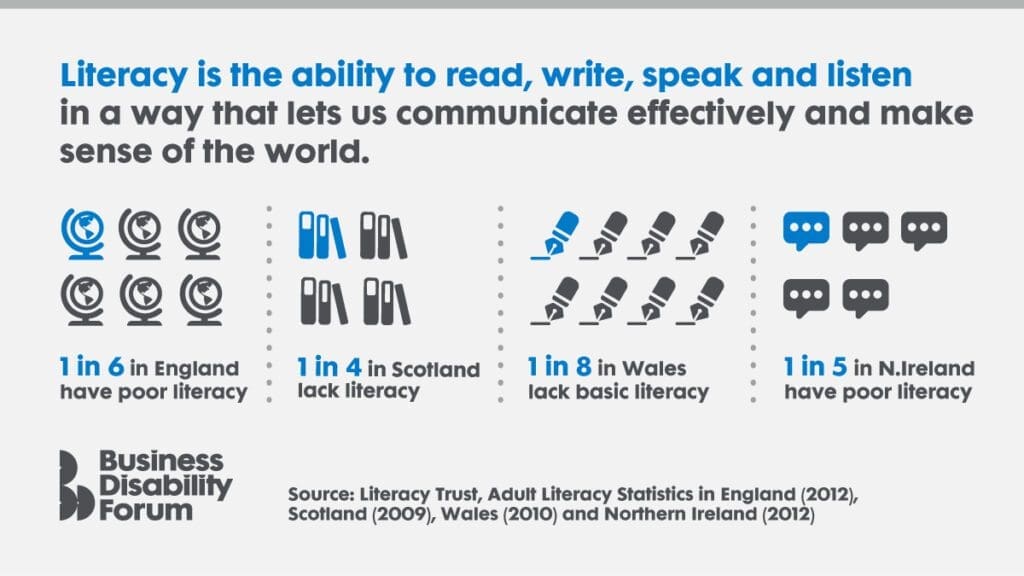

National Literacy Trust explains literacy as ‘the ability to read, write, speak and listen in a way that lets us communicate effectively and make sense of the world’.

Writing in an accessible way can be particularly important for people who have lower levels of literacy. This includes people with learning disabilities and people who have dyslexia.

It may also include people who do not speak English as their first language if that is the language you are communicating in. It is important to note that for many Deaf people in the UK, British Sign Language (BSL) is their first language.

The latest available statistics for adult literacy levels show that:

- 1 in 6 adults in England have poor literacy skills.

- 1 in 4 adults in Scotland experience challenges due to their lack of literacy skills.

- 1 in 8 adults in Wales lack basic literacy skills.

- 1 in 5 adults in Northern Ireland have very poor literacy skills.

You may not know that someone has literacy difficulties and they may not want to tell you. It is up to you to make the information you create as easy to understand as possible.

How to write in an accessible way: Top Tips

The following tips will help you make your writing more accessible:

- Use language which is appropriate for your audience. This may mean writing about the same thing in different ways, for different people. If in doubt, use everyday language instead of formal language.

- Avoid jargon. In some cases, the use of technical language can be appropriate. Only use it if you are sure your audience will understand it and benefit from it. If in doubt, don’t use it or include a glossary.

- Avoid overly long or complex sentences. They are difficult to read and understand. Break them down into several shorter sentences. Plain English Campaign recommends varying sentence length and an average sentence length of 15 to 20 words.

- Use warm and personal language. Avoid referring to someone in a generic way. Instead of terms like ‘customer’, ‘client’, ‘patient’, ‘user’ or ‘employee’, use the person’s name or ‘you’. Refer to yourself as ‘I’ or ‘we’. Some people can find abstract terms difficult to understand and alienating.

- Get to the point. Make it clear what your communication is about and what you want the person to do as a result of reading your communication. Give clear instructions.

- Replace long paragraphs with bullet points. They are easier to read.

- Avoid colloquialisms or metaphors. They may not be culturally relevant to your audience. Some people may take them literally.

- Avoid abbreviations or acronyms. They can be a useful shortcut if used with an audience that understands them. Otherwise avoid them or make sure you explain them.

- Use active rather than passive language. Example: ‘I sent the email to you yesterday’ is easier to understand than ‘The email which you should have received from me yesterday’.

- Avoid capitalising whole words. Capital letters can be more difficult to read and can slow down the reader.

- Tell the person how to access the information in a different format. You can find information on alternative formats in the ‘Practical Resources’ section of this toolkit.

- Use Plain English Campaign guidelines. Plain English Campaign has created several free guides to writing in a clear and concise way.

How to use design features to create accessible communications

How a piece of communication looks can be as important as what it says when it comes to accessibility.

We can make text easier to read by presenting it in an accessible way. The use of colour, and images can also make our communications clearer if used in the right way.

About this resource

This resource if for:

- Anyone who writes or designs content.

- Anyone who wants to understand more about accessible design features or is briefing internal or external design teams.

- Communication, marketing, and web teams.

- Anyone interested in disability inclusion.

In this resource we cover best practice around accessible design features. This includes how text, layout, colour contrast, images, and alternative formats can be used to make your communications more accessible. There is also a short checklist to use when designing your own communications. There are links to other useful resources throughout.How we read text

Text alignment

Most people in the UK read from the left of the page to the right. This means that when text is aligned to the left, it is easier for our eyes and brain to read.

We often have to work harder to read centred text where the position of the start of the line changes from line to line. Justified text can cause similar problems because there is no uniformity in the spacing between words.

For people who have sight loss, dyslexia or a learning disability, trying to adjust to different spacing can be particularly difficult and confusing.

Letter shape and size

In a similar way, font choice can affect the readability of content.

Simpler fonts, such as Arial, Calibri, Helvetica and Verdana, are often considered more accessible than more complex fonts, such as Times New Roman and Garamond.

Spacing out your text can also make it easier read.

As a general rule, use as few different fonts as possible and pick fonts that are commonly available.

Use a minimum font size of 12 points/16 pixels to make it comfortable for the reader. Use 18 point/24 pixels or above for anyone needing large text.

Emphasis

The use of Italics and underlining can also change how a word looks and make it more challenging to read. Capitalising whole words or pieces of text can have the same effect.

It is better to write in sentence case and then use colour contrast, increased font size and bold options to emphasise words.

Layout

To make your text easier to read:

- Layout text in a logical order.

- Use titles, sub headings, numbering and bullet points help the reader stay focused.

- Breakdown information into small, manageable chunks.

How we view colour

Colour contrast

Using colour can help to make information clearer and more interesting. Colour may also be a key part of your organisation’s brand identity.

But it is important to remember that we all view colour differently.

People with sight loss or colour blindness can find it difficult to differentiate between colours with low contrast such as red and green. Light-coloured text on a light-coloured background can also be problematic.

Whereas people with dyslexia and people with learning disabilities may be sensitive to high colour contrast, such as black text on a white background. A dark grey on a cream background may work better.

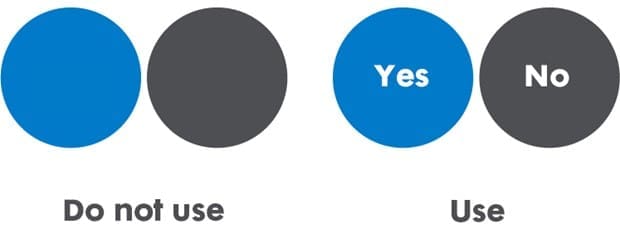

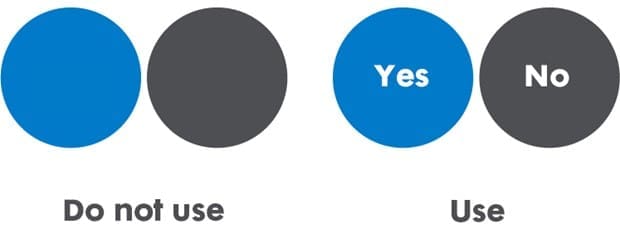

Using colour to strengthen your message

Use colour and colour contrast to strengthen your message. But avoid using colour on its own e.g ‘tick the blue circle for yes and the grey circle for no’. In this example, the words ‘yes’ and ‘no’ should also be written on the circles to make it accessible to anyone who cannot differentiate between colours.

Colour in digital material

Back-lighting means that colours appear differently in printed material than they do in digital documents and online.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, better known as WCAG, are a recognised standard for making online information more accessible to disabled people. WCAG 2 sets a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for standard text. The ratio is based on brightness of text compared with background colour (and vice versa).

Web Aim has written an article explaining contrast ratio and how it applies to larger text, decorative text, logos and graphics. You can also use Web Aim’s contrast checker to check the accessibility of your own colour combinations.

Find out about Skipton Building Society’s work with colour contrast in the case study section of this toolkit.How images can help

Emphasising the message

Including images in a piece of text can help to emphasise the message. They can also make information easier to understand and can be particularly useful for people with low levels of literacy, including people with learning disabilities.

It is best to avoid laying text over an image. If you do need to do this, then place the text in a text box of contrasting colour.

Alternative text (alt text)

Many disabled and non-disabled people use screen readers. These are assistive technologies which read out text in digital documents and websites. Screen readers are particularly useful for people who are blind, people with sight loss and people who have dyslexia.

Screen readers can only read text. They cannot read images. If you include a non-decorative image in a document, you should also include ‘alternative text’. This is also known as ‘alt text’. Alt text describes the image in words and so makes images accessible for people who use screen readers.

You can find out more about alt text in the ‘How to use images in an accessible and inclusive way’ resource above.

Offer alternatives

Even if you follow all the advice in this resource, it still may not be possible to create a document that is accessible to everyone. It is much better to offer the information in other formats, so people can choose the best one for them.

Alternative formats include audio, video, Easy Read and large text.

You can find out more in the ‘Alternative formats: What they are and why they are important’ resource in this toolkit.Design features accessibility checklist

Use

- A logical layout with headers, numbering and bullet points to help order information.

- Left aligned text.

- San serif fonts

- A minimum font size of 12 point/16 pixels

- Bold, colour, and increased font size for emphasis.

- Good colour contrast. Remember this may be different for different people.

- Helpful images to support your message.

- Alt text to make images accessible for people who use screen readers.

Avoid

- Capitalising whole words or sections of text.

- Using italics and underlining for emphasis.

- Colour combinations with low colour contrast.

- Checking colour contrast by sight only. Remember everyone views colour differently and colour looks different in print than in digital documents.

- Using colour on its own to communicate information.

- Using non-decorative images without alt text.

Remember

- Give people choice by offering information in alternative formats.

Alternative formats: What they are and why they are important

Under the Equality Act, there is a legal duty on organisations to make information accessible to everyone, including disabled people. This can be difficult if you are only offering the information in one format.

People with different disabilities and conditions have different communication needs. By making a letter or a video more accessible for one person, you may be making it less accessible for another.

To make sure everyone can access the information they need, it is best practice to offer information in other formats. These are often referred to as ‘alternative formats’.

Keep in mind, that the more you think about accessibility when creating your original piece of communication, the less demand there will be for other formats.

About this resource

Is this resource, we will look at some of the alternative formats you may wish to offer. We will also discuss which people may find them useful and why.

Throughout this resource, you will find links to places you can go to find out more about each format and organisations that can help. There are also links to the case study section of this toolkit.Which alternative formats should I offer?

Read more below.

Be realistic

There are many alternative formats available. Producing every piece of information, in every format, would be impractical, time consuming and expensive.

Instead, you need to decide which formats are the most relevant to the audiences you are communicating with. The best way to do this is to ask your different audiences about their preferred formats. You can do this via your disability and customer networks. Also include your communications team.

In general, offer documents in alternative formats which are the most popular and easiest to produce. This may include:

- Printed versions of digital information.

- Large print versions.

- Information printed on different colour backgrounds.

- Accessible video and audio content.

- Sending information via email or SMS for screen reader users.

You should then provide contact details so someone can let you know if they need information in another format.

If you are simply sending an email to a small group, then adding a sentence to let people know that you are happy to convey the information in a different way, is usually sufficient.

If you are planning a big piece of communication, then plan in alternative versions from the beginning. Try to make sure that the other formats are ready to use when you launch your main piece of communication.Different alternative formats: An overview

The following is an overview of some of the most common alternative formats.

Printed versions

It is important to continue to offer printed versions of information even in this digital age. The percentage of the disabled people using the internet is increasing. But disabled people are still less likely to access the internet than non-disabled people according to ONS research.

Large print and giant print

Large print means using a font size of 16 to 18 point. Giant print is 18 point and above. Both can be useful for people with vision conditions or sight loss.

You can find out more information about large and giant print from the RNIB.

Coloured paper

Black text on a white background can be difficult to read for some people, including people with dyslexia and people with learning disabilities. A dark grey font on a cream coloured background is often more accessible.

Text printed on a bright coloured background can be clearer for people who find it difficult to differentiate between colours with low contrast. This includes people who are colour blind or who have sight loss.

Ask what works best for the individual.

Video and audio content

Some people find video and audio content easier to understand than written content.

Video content, including animations, can be particularly useful for people with learning disabilities, people with dyslexia and people who are accessing content that isn’t in their first language.

Audio versions can be especially helpful for people with visual impairments or sight loss.

Like written content, video and audio must also be accessible to make it usable for as many people as possible. You can find out more in the ‘How create accessible video and audio content’ resource.

Easy read and Makaton

Easy read and Makaton make information easier to understand for people with learning disabilities.

Easy read

An easy read version of a document is a summary of the key points presented in images and simple sentences. Easy read is used to make information easier to understand for people with learning disabilities, but many other people also find it helpful.

In an easy read document:

- Images usually appear to the left of the text.

- Text is 16 points or bigger.

- Fonts are clear and easy to read

- Each image expresses only one idea.

- Text is written in plain English.

- Difficult words or concepts are highlighted and explained.

You can find an example of an easy read template and examples of easy read documents in the case study section of this toolkit. These have been kindly provided by Dimensions.

You can find out more about creating easy read information from organisations such as CHANGE and Photosymbols.

Makaton

Over 100,000 adults and children with learning disabilities use Makaton. Makaton is made up of signs and symbols and is used alongside spoken language to increase understanding.

The Makaton Charity has more information on using Makaton.

British Sign Language (BSL)

According to the British Deaf Association, British Sign Language (BSL) is the preferred language of 87,000 Deaf people in the UK. The BSL Act 2022 recognises British Sign Language as a language in its own right in England, Scotland and Wales

Most BSL users have been Deaf since birth and for many it will be their primary form of communication. As a result, BSL users may prefer to receive a BSL interpretation of a piece of information rather than a version written in English.

BSL signing can be added to a video, alongside captioning and audio description.

There are different national and regional sign languages. This is important if you are creating content for a global audience. Do not assume that a user of BSL will be able to understand American Sign Language (ASL) for example.

You can book in person and online BSL services through SignLive and RNID

Signly’s online tool can create BSL translations of your web pages.

Braille and Moon

Braille and Moon are tactile codes. They are used by some people who are blind or who have sight loss to read using touch.

Braille

According to statistics from the RNIB, around seven per cent of people who are registered blind or partially sighted use braille.

Braille uses a system of raised dots which a person touches with their fingers. Braille takes up more room on a page than written text.

Braille documents can be expensive to create. It is best to check the demand before creating the document and to use the specialist translation services of organisations such as the RNIB.

Moon

Moon uses a tactile system of raised shapes and symbols. It is less widely used than Braille.

SMS and email

Some people with very limited sight as well as people who are blind may find printed material inaccessible and they may not be users of braille. Sending printed material as a digital Word document or via a SMS message or email means the person can use their own assistive technology, such as a screen reader, to access the information. Screen readers read out text. Sending information this way also allows the person to control the font size and text colour etc.Further information

- There is further guidance available on accessible formats from the UK Government.

- The UK Association for Accessible Formats has published a series of standards.

How to use images in an accessible and inclusive way

Using images within your piece of communication can be a great way of reinforcing your message and keeping your audience engaged.

Some disabled people find the use of images particularly useful. This includes people with learning disabilities and some people with neuro-diverse conditions, such as dyslexia. They can also be helpful to people with lower levels of literacy, including people who do not speak English as their first language.

But it’s important to make sure that the images we are using are inclusive and accessible to everyone.

About this resource

This resource offers advice to:

- Anyone who creates digital documents and content.

- Anyone who commissions content from internal teams or external agencies. Please do share this resource with them.

- Anyone interested in accessibility and inclusion.

In this resource you will find advice and tips on using images in an accessible and inclusive way. This includes tips on representing disabled people and writing ‘alternative text’ (alt text). We include links to other relevant resources from the Inclusive Communication Toolkit throughout the resource. We also include links to external research and guidance.Inclusive images

The images we see influence how we think about the world.

Disabled people are underrepresented in the everyday images which we see around us – on TV, on billboards and in marketing literature. According to research carried out by Yahoo Ad Tech, Getty Images and the National Disability Leadership Alliance in the US, disabled people appear in less than 2 per cent of images we see in the media.

If disabled people are represented then it is often as someone ‘vulnerable’ or ‘sick’. Or, at the other extreme, as a ‘superhero’, inspiring everyone with their ‘achievements’.

This means that the needs of disabled people can be overlooked or misrepresented; leaving a large group of people excluded as consumers, employees and in society generally.

Thankfully, this is beginning to change and we can all play our role through the images we choose to use.

It also makes good business sense. If you want someone to respond positively to you, whether as a customer, client, colleague or employee, then that person needs to feel included, valued and understood. Research suggests that 7 out of 10 people feel more positive towards a brand if its advertising includes disabled people.

Representing disability in images: Top tips

Here are some points to consider when using images:

- Check that disabled people are represented in the images you are using. This should include people with different disabilities and people of different races, age, gender identity, sexual orientation and culture. Remember that not everyone with a disability uses a wheelchair.

- Always use real people with disabilities in your images. Do not ask someone to ‘pretend’ to have a disability.

- Check that your images give out a positive message about disability. Avoid images which portray people as ‘victims’ or ‘helpless’, or which patronise.

- Use realistic images of people doing everyday things. Avoid ‘inspirational’ images or images which suggest that disabled people are ‘superheroes’.

Accessible images

It is important to make sure that disabled people are realistically represented in any images you use. It is also important to check that the images you are using are as accessible to as many people as possible.

Images should always support the message being expressed elsewhere in text. They should not be confusing, complicated or be the only means of expressing a piece of information. If they are, then many people will miss what you are trying to say.

Making images accessible: Top Tips

Here are some tips to help you make sure your images are as accessible as possible:

- Only use high quality, clear images.

- Avoid images which are blurry or have shading. These can be difficult for some people to see and confusing for others.

- Check that there is sufficient colour contrast in your images and the image is well lit. Remember that images will appear differently in digital documents than they will in printed material. Also remember that we all see colour differently. Go to ‘How to use design features to create accessible communications’ above for more information on colour contrast.

- Avoid using colour as the only way to express a piece of information. ‘Click the red image’ could prove challenging for someone who is colour blind. Use instead, ‘click the red triangle’ with the alternative being a green square for example.

- Make sure you have provided an ‘alternative text’ (alt text) description of any non-decorative images for anyone using assistive technology, such as screen readers. There is more information on how to create alt text and other text descriptors later in this resource.

- Use actual text in your images rather than images of text. Actual text reduces the need for alt text and is still readable when enlarged.

- Be careful when overlaying an image with text as the text may become difficult to read. Place your text on a block of contrasting colour instead.

What is alternative text (alt text)?

‘Alternative text’ (alt text) is 1 or 2 sentences of written text which describe an image in context. Alt text is helpful for anyone using a screen reader to access your content.

Screen readers are a type of assistive technology. They are used by many disabled people, including people who are blind and people with sight loss to make digital documents accessible. Many non-disabled also use screen readers as a productivity tool.

Screen readers read out text, but cannot read out images. This means that a screen reader user will miss your image, unless you create alt text to describe it to them.

Most programs give you the option to add alt text to your images. If you are creating a Word document in Office 365, for example, right clicking on an image within the document will bring up the option.

How to write alternative text: Top Tips

Describing an image in just a couple of sentences to someone may sound challenging, but it is really important in terms of making your document accessible. Here are some tips to help you:

- Alt text should be no longer than 1 or 2 sentences. If you are using a complex image then a text transcript may be a better alternative. See section below.

- Write alt text using plain English.

- Alt text should be descriptive and specific. Think about the message you a trying to express through the image in this document. Only include information in the alt text which is not included in text elsewhere in the document.

- Alt text should be in context. You might use the same image in several documents on different subjects. Make sure your alt text gives the image context in this particular document.

- Don’t waste words. You don’t need to say ‘image of’ in your alt text. Screen readers will tell the user that it is an image.

- Some programs may suggest alt text for you to use. Always check this for accuracy and meaning before using it.

- Decorative images do not need alt text but must be marked as decorative, otherwise screen readers will read them as a blank. To mark an image as decorative, add two quotation marks like this “” in the alt text box. Some programs also give you a ‘mark as decorative’ option.

- Decorative images include logos, headers, any images which are already described in the surrounding text, and images that are for visual effect only.

Example photo with and without alt text

An image may need alt text if used in one way, but may not need alt text if used in a different context. As the author, you need to decide what purpose the image is serving.

If the above image of a man smiling and holding a phone was being used as an illustration in a resource which talks about your telephone advice service, then alt text would not be needed. The image is just for visual effect.

But if the image was being used on your website to promote a new range of glasses, with the simple header, ‘Take a look at our new range’, the image is providing vital information, which is not included elsewhere, and so alt text should be used. An example of alt text for this image in this context could be:

‘Male wearing rectangular shaped glasses with black plastic frames.’Complex images

If you are using a more complex image, such as an infographic, it may be difficult to summarise the message of the image in two sentences. In this case, it makes more sense to create a text transcript.

A text transcript is simply a text version of the information being conveyed in the image. Text transcript are particularly useful for images which express several different messages in one image.

You can find out more in ‘How to make infographics accessible’ below.Tables and charts

Like infographics, tables and charts often include a mix of words, numbers and visuals to explain information.

It is important to make your tables and charts as clear and as simple to understand as possible – even if they are explaining something very complex. Also consider the design aspects of the table or chart – such as font, font size and colour contrast. You can find out more in our ‘How to use design features to create accessible communications’ resource.

As with infographics, it may be difficult to explain all the information expressed in your chart in just a couple of sentences.

Instead, it is recommended that you use alt text in combination with something called long text or long description.

Alt text with long text

The alt text should explain the overall purpose of the chart or graph – what is it comparing? It should also include the location of the long text.

The long text should then explain the key findings being expressed in the chart or graph.

Including the long text in the text below the image means that it is that can help to make the graph or table accessible to everyone. This works well in a digital document and is easy to create.

If the chart is on a website then a web designer may prefer to create the long text on a separate web page. A link to the web page is then included below the graph.

Example bar chart with alt text and long text

Here is an example bar chart.

Alt text for this could be:

“Bar chart showing the number of calls to the advice line over 4 weeks. The long text is below the image.”

Long text for this could be:

“Bar chart showing the number of calls to the advice line over a 4-week period from customers, employee and other. The x axis shows the week number and ranges from week 1 to week 4. The y axis shows the number of calls from 0 to 100, at intervals of 10.

The chart shows that in weeks 1 and 2 the vast majority of calls are from customers. There are 75 in week 1 and 88 in week 2. The majority of calls in weeks 3 and 4 are from employees. There are 60 in week 3 and 70 in week 4. The number of calls from people which are neither employees or customers remains consistent over the 4 weeks. It ranges from 9 to 12.”

You can find out more about making different types of images accessible in WCAG’s tutorial on images.

How to make accessible infographics

Infographics are a popular tool for presenting complex information in a visual way.

Many people find the use of simple infographics helpful. This includes people who prefer more visual communication, such as some people with learning disabilities and people who have dyslexia.

But infographics can be inaccessible if they contain too much information.

Infographics can also be inaccessible to people who use screen reader software to access digital information. Screen readers are often used by people who are blind and people with sight loss. Screen readers read out text. They cannot read out images or text which displays as an image.

Taking steps to make your infographics accessible means no one misses out on the information you want to communicate.

About this resource

In this resource, we look at ways that you make the content of your infographics accessible to everyone.

We look at the basic principles of accessible design and how they apply to infographics. We also cover using “alternative text” (alt text) and text transcripts, as well as other ways to make infographics accessible. We also include links to other useful resources we have created.

This resource provides an introduction to accessible infographics for:

- Anyone who creates documents, presentations or other content.

- Anyone working with internal or external web editors or graphic designers.

- Anyone interested in accessibility and inclusion.

This resource does not cover how to use computer programming languages, such as HTML or CSS, to imbed infographics in web pages. There is further information on web accessibility for web designers in our resource ‘Accessibility training: A guide to available resources‘.Making infographics accessible

Read more below.

Accessible design

The following best practice tips on accessible design apply as much to infographics as they do other pieces of communication. Time spent on making your infographic accessible at the design stage will mean less time making it accessible later.

Logical layout

- Present information in a logical order. This makes the infographic easier to follow.

Clear text

- Write any text in plain English. This means using simple sentences and avoiding any unnecessary jargon.

- Use serif fonts, such as Arial or Calibri. Many people find these easier to read.

- Use as few fonts as possible to help with readability.

- Use a minimum font size of 12 point to make the text easier to see.

- Write text in sentence case. Avoid capitalising whole words or sections of text.

- Use true text instead of images of text in your infographic. True text gives people greater choice over how they view the text.

Colour contrast

- Use colour and bold options for emphasis, rather than italics and underlining.

- Use colour contrast within the infographic. Text and graphics should be in a contrasting colour to the background, so they can be easily seen.

- Avoid using colour as the only way of expressing a piece of information. This can be difficult for people who are colour blind.

Hyperlinks

- Underline hyperlinks and use a contrasting text colour so links are easy to see.

- The link text should make sense as a standalone phrase. It should also tell people where they will end up if they click on the link.

Other formats

- Provide a text alternative of your infographic for anyone who cannot access the image.

- Consider offering the information in your infographic in other formats.

These tips are covered in more detail in ‘How to use design features to create accessible communications’ above.

Using alt text

Including “alternative text” (alt text) is one way to make your infographic accessible to people who use screen readers.

Screen reader software reads out the alt text in place of the infographic. If no text is provided the screen reader will just miss out the infographic completely.

Alt text should be 1 or 2 sentences which explain the contents of the infographic to someone who cannot see it.

Alt text is best used to describe simple infographics which contain only one piece of information or message.

Here are some tips on creating good alt text for your infographic.

- Alt text should be concise. It should be just 1 or 2 sentences long.

- It should be written in plain English.

- It should be descriptive and specific. What do you want people to know about your infographic from your alt text? What is the message? Only include information which is not included in text elsewhere.

- Don’t waste words. You don’t need to say ‘infographic of’ or ‘image of’ in your alt text. The screen reader software will tell the user that it is an image.

Here is an example of a simple infographic, which expresses just one message.

Alt text for this infographic could be:

The number of disabled people using the internet is increasing. There were 10 million people in 2019. This increased to 11 million in 2020.

You can find out more about writing alt text in ‘How to use images in an accessible and inclusive way’ above.Text transcript

A text transcript is the other way to make your infographic more accessible.

A text transcript is simply a text version of your infographic. Text transcripts are a good way to make more complex infographics, which express more than one piece of information, accessible to screen readers. They can also be useful to anyone who may find your infographic difficult to understand.

The text version can sit below the infographic. A screen reader will then just read it out as it would any other text.

Here is an example of an infographic, which expresses more than one piece of information.

A text transcript for this infographic could be:

National Literacy Trust describes literacy as “the ability to read, write, speak and listen in a way that makes lets us communicate and make sense of the world.” Statistics on adult literacy show that:

- 1 in 6 adults in England have poor literacy skills.

- 1 in 4 adults in Scotland experience challenges due to their lack of literacy skills.

- 1 in 8 adults in Wales lack basic literacy skills.

- 1 in 5 adults in Northern Ireland have very poor literacy skills.

Infographics as PDFs

You will need to use a professional program, such as Adobe Acrobat Professional, to turn your infographics into an accessible PDF.

You can find out more about tagging PDFs in our video ‘How to tag PDFs for accessibility’, which is below.Offering alternatives

As the above shows, there are several ways to make an infographic more accessible. Some are relatively simple. Others require more technical knowhow and access to particular software.

If you are creating an infographic then it is important to take reasonable steps to make it as accessible as possible.

It is important to note, though, that all the methods mentioned in this resource have their advantages and their disadvantages.

It is actually very difficult to recreate the full visual experience which an infographic can offer, just by using text, for example. Other methods may be beyond your reach, unless you are a skilled web or graphic designer.

Also, you may do your best to produce an infographic which is accessible and still find that it does not work for some of your audiences.

For these reasons, it makes sense to consider presenting the information in your infographic in other formats as well.

Here are two alternatives you could consider:

- An Easy Read version. Easy Read uses short, simple sentences accompanied by helpful images. Each message in the infographic could be broken down in this way.

- A captioned video or animation. This could be an alternative to a complex infographic. You have more control in a video or animation over the order in which the audience receives the information.

There is more information on alternative formats in ‘Alternative formats: What they are and why they are important’ above.

How to create accessible video and audio content

More of us are watching videos and listening to podcasts than ever before.

Video and audio content can make complex information easier to understand. It can be particularly useful for people with learning disabilities and for people who find written content difficult to understand, for example.

But it can also present real challenges for some disabled people. This includes people who are blind or who have sight loss as well as people who are deaf or have limited hearing.

It is also important to remember that there are times when we may all prefer or need to view content with the sound turned off. By making content accessible, we are making it work better for everyone.

About this resource

This resource offers advice to:

- Anyone who creates video or audio content.

- Anyone who commissions content from internal teams or external agencies. Please do share this resource with them.

- Anyone interested in accessibility and inclusion.

In this resource, you will find guidance on how to make your video and audio content more accessible. This includes links to information from other organisations. You will also find a short checklist at the end of the resource.

W3C’s resource on accessible audio and video gives further advice on planning your content and meeting the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) standard.Making video and audio accessible

Thinking about the following areas will help to make your videos, animations and audio content accessible to as many people as possible.

Avoiding jargon

Speak in plain English and avoid any unnecessary jargon. See our resource ‘How to write in an accessible way’ above for more on this topic.

Sound quality

Make sure all speech can be heard. Ask people to speak clearly and slowly. Try to keep any background noise to a minimum.

Captions

Include captions. Captions are a text version of any words spoken. The captions play at the same time as the video or audio content. They usually appear at the bottom of the screen.

Captions are useful for everyone as they allow you to watch a video or a webinar with the sound turned off or in a noisy environment. They are particularly useful for people who are deaf or who have hearing loss.

Closed captions can be turned on and off by the viewer as needed. The viewer also has more control over how the captions look. This article by WebAIM explains the use of captions in more detail.

Consider font type (font family), font size and colour contrast when creating your captions, so they are as easy to read as possible. Find out more in ‘How to use design features to Design features to create accessible communications’ above.

Most platforms have options to upload content with captions or to create captions within the platform. This includes Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and TikTok.

Try to avoid using auto captioning if time and budget allow. If you do use it then make sure you check and edit it for accuracy.

This video on the Business Disability Forum website helps to explain the importance of captioning. It was created by Microsoft, in partnership with the Business Disability Forum, NatWest Group, Barclays, PwC, and Eli Lilly and Co.

Transcripts

Provide a transcript. Written transcripts are an easy way to make audio content, such as podcasts, more accessible to people who are deaf or who have hearing loss. But they are useful for everyone. Transcripts allow people to read content at their own pace and to revisit information.

Providing captions and transcripts for your media content can also help to increase traffic to your website as it makes your content more searchable.

Many platforms now provide an auto transcript option. These must be checked for accuracy before being relied upon.

Audio description

Use audio description. Audio description explains what is going on visually in a video. You don’t need to include everything, only the information which is needed to understand what is happening in the film.

Audio description should be written in the present tense and in a third person active voice.

Our Disability Smart Awards 2023 video (hosted on YouTube) shows how audio description, captions, and a transcript can be used to make a video more accessible.

Animations

Like video and audio content, animations can help to make your content more engaging and easier to understand. But animations can also cause problems for some disabled people. The motion element of animations can be overstimulating for some people.

WCAG guidance on animation recommends that you give the viewer control over the animation. This means putting in functionality to allow the animation to be stopped or paused or turned off altogether. Also make sure that keyboard users can control animations with just their keyboard.

Flashing images

Flashing images can cause life threating seizures for people with epilepsy and are best avoided. Epilepsy Action has more information on using flashing images safely.Inclusive content

As well as making your content accessible, it is also important to think about the representation of disabled people within your content.

Research carried out by Yahoo Ad Tech, Getty Images and the National Disability Leadership Alliance found that disabled people appear in less than 2 per cent of images we see in the media.

Business Disability Forum’s research into the spending habits of disabled people found that 1 in 3 disabled did not feel that businesses advertised to them.

You can help to change the perception of disability by including disabled people in your content and portraying them in a positive and realistic way.

This will also help you better engage with disabled and non-disabled customers and employees. The Getty Images research suggests that 7 out of 10 people feel more positive towards brands if its advertising includes disabled people.

You can find out more on representation in ‘How to use images in an accessible and inclusive way’ above.Additional ways to make content accessible

If time and budget allow, then you might also want to consider these additional ways of making your content accessible.

British Sign Language

British Sign Language (BSL) is the main and preferred form of communication for many people who are Deaf from birth.

Including a BSL signer in your video can help make your film more accessible to this audience. The signer is usually included in the corner of the screen.

It is important to remember that there are different national and regional sign languages, so BSL may not work for every Deaf person.

Descriptive transcripts

This is a written transcript to go with a video. It explains what is happening in the video and can help make the video accessible to anyone who may find the content difficult to follow.Checklist for creating inclusive and accessible video and audio content

- Are you using plain English?

- Is the sound quality good?

- Has background noise been kept to a minimum?

- Have you included closed captions in your video?

- Have you included audio description in your video?

- Have you provided a transcript for your audio content?

- Are disabled people represented in a positive and realistic way in your content?

- Is the viewer able to control any animated content?

- Have you avoided flashing imagery?

- Would your video benefit from a descriptive transcript?

- Could you include BSL signing in your video?

Understanding diverse communication needs

For some people, having a disability or long-term condition may affect the way that they communicate, receive, and process information. Up to 20 per cent of the UK population will experience communication difficulty at some point in their lives according to Communication Access UK.

It may not always be obvious that a person has a communication need, so it’s important to not make assumptions and to offer choice to all customers and colleagues over how they communicate with you and receive information.

Offering information in a variety of formats and using a range of different communication channels will make sure your communication is clear and effective.

About this resource

This resource is for:

- Anyone who wants to gain a better understanding of different communication needs.

- Anyone who creates internal or external communications.

- Those responsible for improving customer or employee experiences.

In this resource we will look at some of the most common communication needs that people with different disabilities and long-term conditions experience. We will also consider how you can meet peoples’ needs through the way you communicate and the channels you use. Offering information in alternative formats, such as BSL, large print, video, and Easy Read is vital. You can find out more in our resource ‘Alternative formats: What they are and why they are important’ above.

Understanding diverse communication needs: Things to consider

- The responsibility is on you and your organisation to make sure the information you provide is accessible to your customers and employees.

- Not providing information to people in a format they need means your message may misunderstood or ignored.

- Thinking about the diverse ways people communicate, receive and process information, early on, will save you time and resources later.

- Always check how a person would like receive information from you and communicate with you.

Diverse communication needs

Here are some of the ways that having a disability or long term may affect a person’s communication needs and preferences.

People with autism

- The National Autistic Society states that one in 100 people in the UK are on the autism spectrum.

- People with autism process information in a different way. This can affect how a person receives and communicates information.

- A person with autism may need extra time to process information and may prefer to receive an email or letter rather than an unexpected telephone call.

- Written communication should give clear and direct instructions. Explain why you are sending the information and how you would like the person to respond.

- Information may be interpreted in a literal way so avoid using abstract phrases.

- People with autism can be over-sensitive or under-sensitive to sights and sounds. It is important to consider this when creating any audio or video content. Provide a short text summary of the content, so the person can decide whether they want to access it.

People who are blind or who are partially sighted

- According to the RNIB, over 2 million people in the UK are living with sight loss, which affects their daily lives. Around 340,000 people are registered blind or partially sighted

- Sight loss is the loss of vision that cannot be corrected with treatment or corrective lenses. It can be present from birth or acquired at any age.

- There are varying degrees of sight loss. Most people still have some sight, but it may be blurred, limited or changing.

- People who are blind or partially sighted may find standard sized text difficult to see and read. They may prefer to receive information in large print (18 point +), on bright coloured paper or as an audio file. Around seven per cent use Braille.

- Findings from WebAIM’s survey show that people who are blind or who have low vision are the greatest users of screen readers globally. Screen readers are a form of assistive technology which turn digital text into speech.

- Many people with vision conditions like receiving information in a Word format as they are able to control the font size, font type and colour options.

People who are colour blind

- Colour blindness affects approximately 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women in the world according to Colour Blind Awareness.

- Colour blindness affects how a person views colour and differentiates between colours.

- Most people who are colour blind are red/green colour blind. This means they find it difficult to differentiate between red and green, but also colours which have some element of red or green in them.

- It is important to be aware of colour blindness when using colour to express information.

- Never use colour alone to express a piece of information. Always support it with text or a visual, such as shape.

People who are deaf or have hearing loss

- The number of people living with hearing loss is expected to grow to 1 in 5 by 2035 according to RNID and ONS estimates.

- A person who has some hearing may use a hearing aid to help them communicate.

- People who have profound deafness are more likely to use lip reading or a form of sign language interpretation.

- Most people who use sign language have been Deaf from birth and may not consider it to be a disability. Sign language may be their primary and preferred form of communication over written information.

- British Sign Language (BSL) is the most common form of sign language used in the UK. It is the preferred language of over 87,000 Deaf people and is now recognised as a language in its own right in England, Scotland and Wales . Different forms of sign language are used in other countries and there are also regional dialects.

- Note that there are two spellings of deaf. Big D Deaf is most often used to describe someone who is born with deafness and identifies as part of the Deaf Community. Smaller d deaf is a broader term and describes someone who identifies as part of the hearing community. If in doubt, and if necessary, ask the person how they would like to be described.

- Videos can be made accessible to people with hearing loss by including captions, audio descriptions and BSL signing.

- Audio files can be made more accessible by offering a text transcript.

- Many people with hearing loss use apps on their phone to help them communicate during social, meetings or work situations. Make sure people are allowed to use their phone to do this.

People with dementia

- The Alzheimer’s Society estimates that there are 900,000 people with dementia in the UK and the number is rising as the population ages.

- Dementia can affect a person’s ability to remember information as well as their ability to communicate and process it.

- Using short and simple sentences can help when communicating with someone with dementia.

- Avoid correcting the person. Instead, repeat and rephrase information when needed.

- Try to limit the number of choices being offered. Too much choice can cause confusion.

- Use images and other visual clues to help with understanding.

- Use a person’s name when communicating rather than ‘he’ or ‘she’.

- Look out for non-verbal cues such as pointing and gesturing. Use non-verbal cues to help with understanding.

- Dementia can also affect a person’s ability to write and process written information. Using plain English and large print can help.

People with dyslexia

- One in 10 people in the UK have some level of dyslexia according to the NHS .

- People with dyslexia process information differently. The areas primarily affected are reading, writing, spelling, numeracy and personal organisation.

- People with dyslexia often prefer information presented in a visual way rather than chunks of heavy text.

- Documents should be clearly laid out and follow a logical order.

- Some people have a sensitivity to colour. They may find black text on white background difficult to process. Try using dark grey on a cream background instead.

- Some people with dyslexia use text to speech software, such as screen readers, to help them access written information.

- People with dyslexia may need longer to process information. Consider this when setting the timing of captions on videos.

- Providing audio versions of information can also be helpful.

People with learning disabilities

- It is estimated that at least 1.5 million people in the UK have a learning disability according to the Foundation for People with learning disabilities. A learning disability can be mild, moderate or severe. Up to 350,000 are thought to have a severe learning disability and this number is increasing.

- Having a learning disability may affect how someone processes information and how they communicate.

- Most people with learning disabilities live independently, with or without support.

- Providing an Easy Read summary can help make complex written information easier to understand for people with learning disabilities. Easy Read uses simple sentences with explanatory images.

- Providing information in an accessible video format can also be helpful.

- Makaton is a form of sign language used by some people with learning disabilities. It is made up of signs and symbols and is used alongside spoken language.

People who stammer

- Up to 2 per cent of adults in the UK stammer according to statistics from Stamma.

- Stammering is when a person gets stuck with words or repeats words.

- More men stammer than women.

- Stammering is a neurological spectrum condition. It can vary from one person to the next and from day to day.

- Be patient if speaking with someone who stammers. Let the person speak and finish what they saying. Do not interrupt them.

- Telephone calls can be particularly difficult for people who stammer. There may be a delay when the person first picks up the phone.

- A person’s stammer may get worse in group situations or when speaking in public.

- Always check the person’s communication preferences.

People who experience stroke or acquired brain injury

- Survivors of stroke or brain injury can experience aphasia or dysphasia.

- Aphasia is a full or partial loss of language.

- Aphasia can affect a person’s use and understanding of speech as well as their reading and writing.

- The Stroke Association estimates that a third of stroke survivors experience aphasia.

- Use short and simple sentences so the meaning of your communication is clear.

- Back up spoken communication with written communication. Using images can also be helpful.

- Be patient. Give the person plenty of time to communicate.

You can find out more about disability and face-to-face communication in our resource, ‘Welcoming disabled customers’.

How to create accessible Word documents

Many of us regularly use Word to create digital documents. Microsoft has bult in many accessibility features into the programme to help you make your document easier to use and navigate.

These features are particularly useful for making your document more accessible to people who are blind or partially sighted and may be using assist technology, such as screen readers, to access the document. They are also useful for anyone who finds written information difficult to navigate. This includes people with dyslexia and people with learning disabilities but also includes many other people.

Using accessible design features will also increase the readability of your document, making it more accessible for everyone.

About this resource

This resource is for:

- Anyone who creates Word documents.

- Anyone wanting to turn a Word document into a PDF or other format or working with other teams or external agencies who create PDF’s. Please share this resource with them.

- Anyone who is interested in accessibility and inclusion.

In this resource, you will find top tips on how to make your Word document more accessible as well as general best practice on accessible design. We recommend that you look at Microsoft’s latest guidance on Word for accessibility information about a particular version of the programme. You will also find more general advice on accessibility and design in ‘How to use design features to create accessible communications’ above.

How to make your Word document accessible

Here are some of the ways that you can make your Word document accessible to as many people as possible. This advice also applies to Word documents that are being turned into PDFs and other formats. The more time spent on making your document accessible now, the less time you will need to spend on accessibility at the PDF stage.

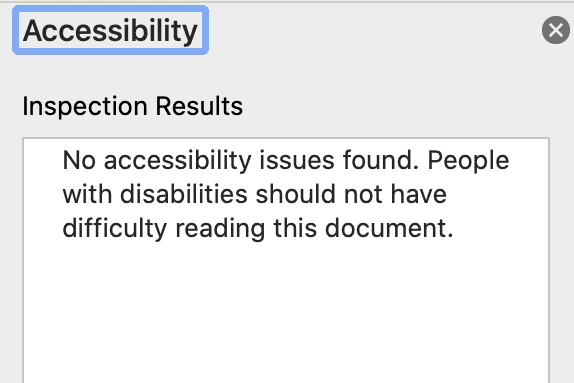

Use the accessibility checker

More recent versions of Word come with an ‘accessibility checker’ built in. The accessibility checker will pick up the most common issues around accessibility.

To turn on the accessibility checker, click on the Review tab in the ribbon at the top of the page and then click ‘Check Accessibility’.

You may find it useful to keep the accessibility checker turned on while you work. This means that you will be alerted to accessibility issues while you are creating your document. Ticking the ‘Keep accessibility checker running while I work’ box will leave keep the accessibility pane open.

The checker will highlight if there are any accessibility issues which need to be investigated. It will also list what the issues are and offer recommendations on how to fix them.

Like all tools, the accessibility checker has its limitations and so it is important to use your own knowledge to check the document too. If you are sending out your document widely then it is best to get it reviewed by your disability network or a customer focus group.

Use accessible fonts

Choose an accessible font. Many people find san serif fonts, such as Arial and Calibri, easier to read that more complex fonts, such as Times New Roman.

Use a font size of at least 12 point. Use 18 point or above if creating a large text document.

Check for sufficient colour contrast

Make sure your text contrasts sufficiently with your background colour. Low contrast can make the text difficult to read for people with low vision or sight loss. Too high a contrast can be distracting and make your document an uncomfortable read for people with neurodiverse conditions, such as dyslexia and autism.

Go to our resource ‘How to use design features to create accessible communications’ above to find out more about how to use fonts and colour.

Write in plain English

Many people find reading complex written information difficult to understand. Writing clearly and simply will help to get your message across more easily.

Avoid overly long or complex sentences.

Explain any unfamiliar terms and abbreviations.

Avoid any unnecessary jargon.

We have created a resource on ‘How to write in an accessible way’ above to help you.

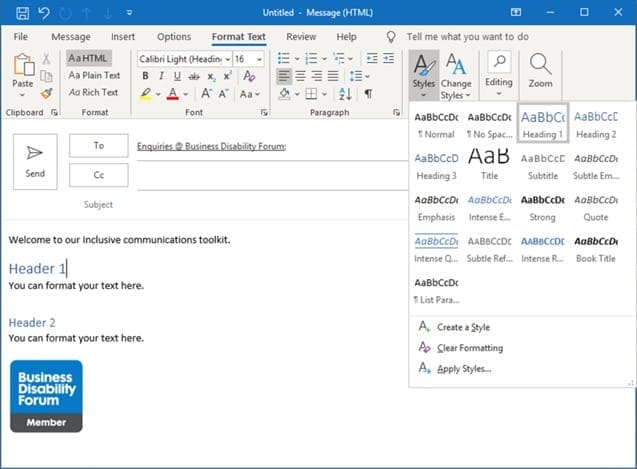

Structure your document

Using the ‘Styles’ feature in Word helps you create a structured document. Structuring your document is important for several reasons:

- A structured document is easier to navigate for everyone, but is particularly useful for screen reader users. Screen readers are a form of assistive technology which read out text in digital documents and online content. They are used by many disabled people.

- A structured document keeps its structure when converted to PDF or web (HTML) formats.

- Reformatting a structured document can be done by modifying the Styles rather having to select the different sections of text within the document.

- Page layout programs, such as Adobe InDesign, can recognise Styles. Using structured documents can speed up the process of reproducing copy for professionally printed material.

Using styles

You can find the ‘Styles’ panel on the Word Home page or by pressing Alt+H, then L.

To use ‘Styles’, highlight the text you want to apply it to and then select the style you want to use.

The ‘Title’ style should be used for the main title of the document.

Then headings styles should be used for all other headings. Headings should cascade in a logical order within a section of the document e.g. ‘Heading 1’ followed by ‘Heading 2’ and so on. New sections should begin with ‘Heading 1’ to identify the start of the different content.

Use relevant style options for lists, rather than the bullet point option on the toolbar.

Use ‘Normal’ for body text.

Keyboard shortcuts for applying styles

You can also use keyboard shortcuts to apply Styles. Listed below are the keyboard shortcuts for the most commonly used styles for Windows. These shortcuts can be modified and tailored to your preferences.

- Ctrl + Shift + N – Apply the ‘Normal’(or document default) style

- Ctrl + Alt + 1 – Apply Heading 1 style

- Ctrl + Alt + 2 – Apply Heading 2 style

- Ctrl + Alt + 3 – Applying Heading 3 style

To use keyboard shortcuts on a Mac computer, replace Ctrl with the command key.

Microsoft’s ‘Keyboard shortcuts in Word’ lists all the most commonly used shortcuts for all versions of Word.

Modifying and creating styles

There are several ways you can modify an existing Style and create your own Styles.

The Design tab offers you different Style sets which can be used in place of the default options. You can also create Styles of your own within the Styles toolbar.

Check guidance from Microsoft on how to modify and create styles for your version and how to set tailored short cut keys for each Style.

Add a table of contents

Adding a table of contents makes longer documents easier to navigate. If you have used Styles and appropriate headings to create your document, the table of contents will be automatically synchronised with the structure of the document. Check it is correct and update it if not.

Using images correctly

Screen readers cannot read images. They can only read text. You need to add ‘alternative text’ (alt text) to any non-decorative images in your Word document to make them accessible for screen reader users.

Alt text is 1 or 2 sentences of written text which describe an image in context. Alt text is read out by screen reader software when it reaches the image.

You can add alt text to images in your Word document by right clicking on an image and selecting ‘Edit alt text’.